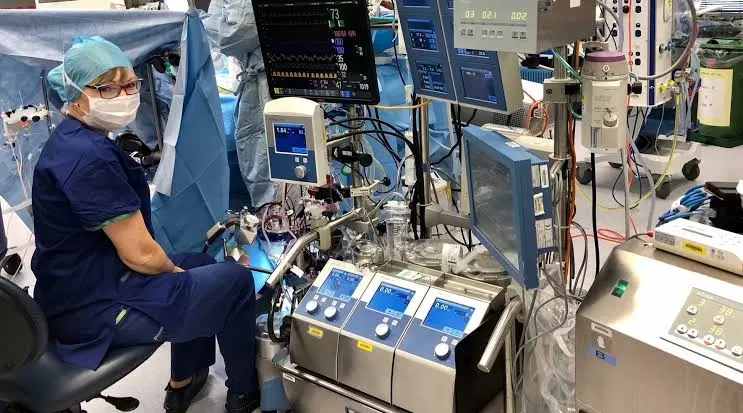

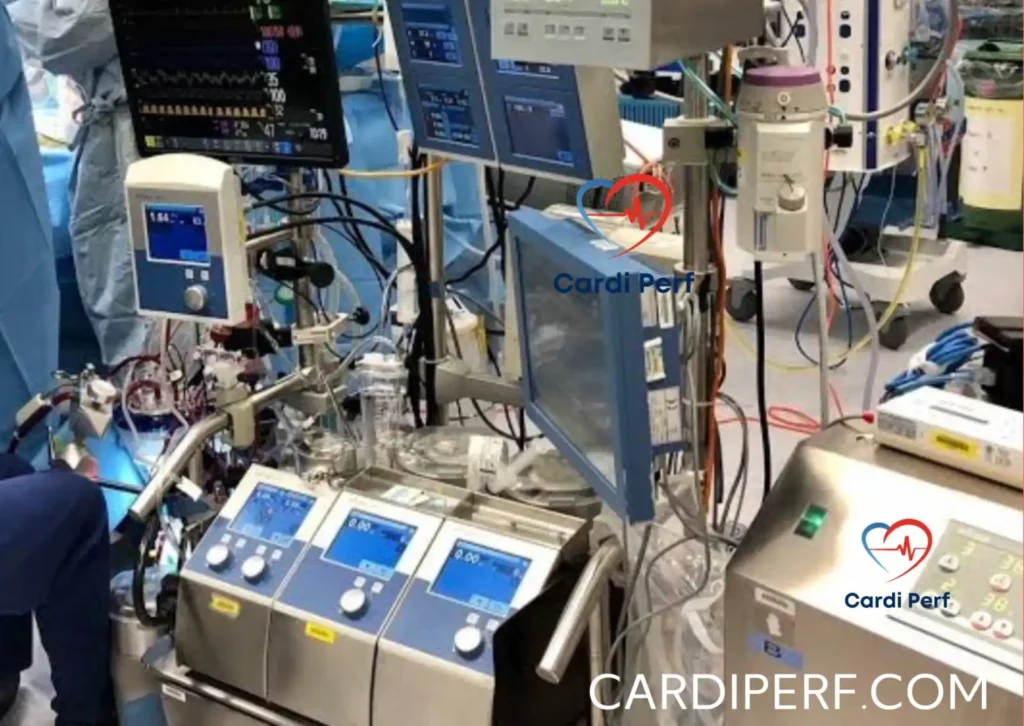

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is a critical component of modern cardiac surgery, allowing for the temporary cessation of cardiac activity while maintaining systemic perfusion and oxygenation. Despite advancements in perfusion technology, surgical techniques, and patient monitoring, hypotension during CPB remains a common and concerning complication. If not managed effectively, intraoperative hypotension can lead to inadequate organ perfusion, ischemic injury, and adverse postoperative outcomes.

This article explores the causes, prevention strategies, and management of hypotension on CPB, supported by a real-world case scenario to illustrate key principles in clinical practice.

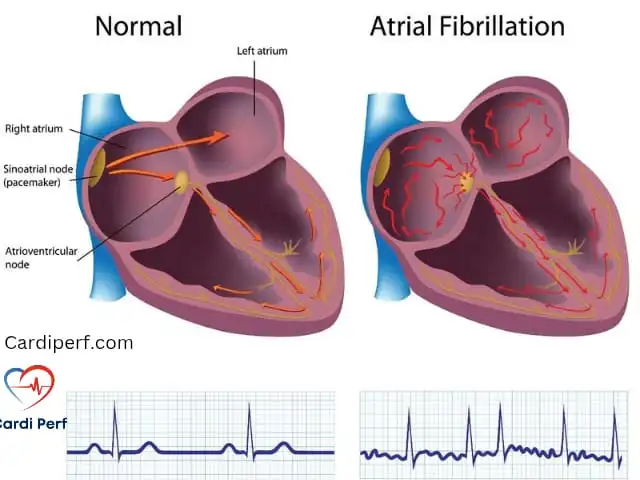

Understanding Hypotension on CPB

Hypotension during CPB is typically defined as a mean arterial pressure (MAP) below 50 mmHg, though the threshold may vary based on patient factors such as age, comorbidities, and surgical requirements. Maintaining adequate perfusion pressure is crucial for end-organ function, particularly in patients with cerebrovascular disease, renal impairment, or other high-risk conditions.

Normal CPB Hemodynamics

Under normal CPB conditions, blood flow is non-pulsatile, and perfusion is managed primarily by adjusting pump flow rates, systemic vascular resistance (SVR), and vasoactive medications. The goal is to maintain an adequate MAP while ensuring sufficient oxygen delivery to tissues.

Causes of Hypotension on CPB

Several factors contribute to hypotension during CPB. These can be broadly categorized into preload-related causes, pump flow-related issues, systemic vascular resistance (SVR) abnormalities, and external factors.

1. Preload-Related Causes

- Hypovolemia: Insufficient intravascular volume due to inadequate venous return, excessive hemodilution, or blood loss.

- Venous drainage issues: Poor venous return due to cannula malposition, kinking, or airlocks in the venous line.

- Inadequate priming volume: Excessive ultrafiltration, hemoconcentration, or improper CPB circuit priming.

2. Pump Flow-Related Causes

- Inadequate pump flow: Low pump flow settings or obstruction in the arterial line leading to insufficient systemic perfusion.

- Cavitation or air embolism: Air bubbles or cavitation in the pump system can lead to transient flow interruptions and hypotension.

3. Systemic Vascular Resistance (SVR) Abnormalities

- Excessive vasodilation: Inflammatory mediators, anesthetic agents, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) can cause profound vasodilation.

- Histamine release: Certain drugs, blood product reactions, or allergic responses may induce histamine-mediated vasodilation.

- Hypothermia: Cold-induced vasodilation may lead to low SVR and subsequent hypotension.

4. External and Metabolic Factors

- Anesthetic effects: Volatile anesthetics and sedative agents may contribute to systemic hypotension.

- Metabolic acidosis: Acidotic conditions reduce myocardial contractility and vascular tone, exacerbating hypotension.

- Calcium abnormalities: Hypocalcemia impairs vascular contractility and myocardial performance.

- Hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia: Glucose imbalances can impact vascular function and hemodynamic stability.

Prevention of Hypotension on CPB

Preventing hypotension during CPB requires a proactive approach that involves meticulous patient preparation, optimized CPB circuit setup, and vigilant intraoperative monitoring.

1. Preoperative Optimization

- Fluid status assessment: Preoperative volume loading or diuretics may be required to optimize intravascular volume.

- Medication management: Reviewing vasoactive drug use and adjusting preoperative beta-blockers or ACE inhibitors to minimize excessive hypotension risks.

- Electrolyte and acid-base correction: Addressing any preexisting metabolic imbalances before CPB initiation.

2. CPB Circuit Optimization

- Adequate priming: Ensuring proper circuit priming with an appropriate balance of crystalloid and colloid solutions.

- Hemoconcentration adjustments: Balancing ultrafiltration and dilution strategies to prevent excessive hypovolemia.

- Cannula positioning: Ensuring correct venous and arterial cannula placement to optimize drainage and perfusion.

3. Intraoperative Monitoring

- Continuous hemodynamic assessment: Monitoring MAP, central venous pressure (CVP), mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2), and blood gases.

- Perfusionist vigilance: Active communication between perfusionists, anesthesiologists, and surgeons to promptly address hemodynamic variations.

- Temperature regulation: Avoiding excessive hypothermia that could contribute to systemic vasodilation.

Management of Hypotension on CPB

When hypotension occurs, a systematic approach should be used to identify and correct the underlying cause promptly.

1. Assessing Venous Return and Pump Flow

- Check venous return: Ensure adequate venous drainage by checking for kinks, airlocks, or malpositioned cannulae.

- Increase pump flow: If pump flow is inadequate, gradually increasing flow rates can help restore perfusion pressure.

- Modify circuit resistance: Adjust arterial line filters or tubing if obstruction is suspected.

2. Adjusting Systemic Vascular Resistance (SVR)

- Administer vasopressors: Agents such as phenylephrine, norepinephrine, or vasopressin can counteract excessive vasodilation.

- Correct acidosis: Administer bicarbonate if metabolic acidosis is contributing to hypotension.

- Maintain normothermia: Gradually rewarming if excessive hypothermia is causing vasodilation.

3. Addressing Metabolic and Electrolyte Imbalances

- Correct hypocalcemia: Administer calcium chloride or calcium gluconate if needed.

- Optimize glucose control: Maintain blood glucose within an optimal range (typically 140-180 mg/dL) to prevent hemodynamic instability.

- Check anesthetic depth: Adjust anesthetic administration to prevent excessive vasodilation.

Real-World Case Scenario

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old male undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) developed sudden hypotension (MAP 42 mmHg) 15 minutes into CPB. Initial assessment revealed adequate pump flow (4.5 L/min) but poor venous return.

Intervention and Resolution

- Venous cannula repositioning: Mild repositioning of the venous cannula restored optimal drainage.

- Volume adjustment: A 250 mL albumin bolus improved intravascular volume and increased MAP to 55 mmHg.

- Vasopressor administration: Phenylephrine (100 mcg bolus) restored SVR, stabilizing MAP at 65 mmHg.

- Rewarming: Gradual rewarming helped prevent persistent vasodilation.

The patient remained hemodynamically stable for the remainder of the procedure and was successfully weaned off CPB without complications.

Conclusion

Hypotension during CPB is a multifactorial challenge requiring prompt identification and intervention. Understanding the underlying causes, implementing preventive measures, and applying effective management strategies are crucial for optimizing patient outcomes. By integrating a systematic approach to CPB hemodynamics, perfusionists and surgical teams can enhance patient safety and minimize complications associated with hypotension during cardiac surgery.

Case Scenario

A 60-year-old patient with progressive angina requiring coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) undergoes a routine induction, intubation, and surgical preparation without complications. Cannulation is performed, and CPB is initiated. However, shortly after, the perfusionist notes an alarming drop in perfusion pressure, struggling to maintain levels above 30 mmHg. Simultaneously, the cardiotomy reservoir begins to overflow, signaling a critical issue. Upon closer inspection, the problem is identified: the recirculation shunt between the arterial and venous lines was left unclamped, a deviation from the standard protocol at the primary institution of the operating surgeon. Once clamped, the perfusion pressure stabilizes, allowing the surgery to proceed as planned.

Discussion

This case highlights the intricate nature of CPB and the potential for human error to disrupt the surgical flow. Despite being a routine procedure, CPB requires seamless coordination among the surgical team, including the surgeon, anesthesiologist, perfusionist, and nursing staff. The following factors contribute to hypotension during CPB and strategies for prevention and management:

Causes of Hypotension on CPB

- Inadequate Systemic Vascular Resistance (SVR)

- Excessive vasodilation due to anesthetic agents or systemic inflammatory response.

- Use of vasodilators or insufficient vasopressor support.

- Mechanical Issues

- Unclamped recirculation lines, as seen in this case.

- Improperly positioned arterial cannula leading to malperfusion.

- Airlocks or kinks in the arterial line reducing effective flow.

- Volume and Flow Imbalances

- Excessive venous return, leading to oxygenator overflow.

- Hypovolemia from inadequate priming or excessive ultrafiltration.

- Insufficient pump flow leading to inadequate perfusion pressure.

- Equipment Malfunction

- Occlusion in arterial filters or oxygenator failure.

- Malfunctioning roller pumps or centrifugal pumps.

Prevention and Standardization

To minimize the risk of such critical events, adherence to standardized protocols and enhanced team communication are essential.

- Checklists and Protocols

- Implement checklists for CPB initiation and weaning to ensure key steps are not missed.

- Standardize perfusion equipment setup across institutions and within surgical teams.

- Preoperative Briefings

- Conduct structured preoperative discussions to align all team members on patient-specific factors and procedural expectations.

- Communication and Teamwork

- Encourage real-time verbal confirmations such as “read-back, speak-back” between team members.

- Foster a culture where any team member can question an unexpected deviation from protocol.

- Real-Time Monitoring and Situational Awareness

- Continuous assessment of perfusion parameters, including pressure, flow, and volume status.

- Frequent communication between perfusionist and anesthesiologist regarding hemodynamic status and interventions.

FAQs

1. What are the most common causes of hypotension on bypass?

- Common causes include vasodilation, mechanical obstructions, volume imbalances, and equipment malfunctions.

2. How can perfusionists prevent hypotension on CPB?

- By adhering to standardized protocols, utilizing checklists, and maintaining continuous communication with the surgical team.

3. What should be done if hypotension occurs during bypass?

- Identify the underlying cause immediately, check for mechanical issues, ensure proper drug administration, and adjust pump flow accordingly.

4. How does communication affect CPB outcomes?

- Clear communication between the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and perfusionist ensures timely interventions and prevents errors that could lead to adverse patient outcomes.

5. What role do checklists play in preventing CPB complications?

- Checklists help standardize critical steps, reducing human error and ensuring consistency in perfusion management.

6. Can equipment malfunction contribute to hypotension on bypass?

- Yes, oxygenator failure, occlusions, or pump malfunctions can significantly impact perfusion pressure and must be promptly identified and corrected.

7. What medications are used to manage hypotension during CPB?

- Vasopressors such as norepinephrine and phenylephrine, as well as volume expanders and inotropes, are commonly used to stabilize perfusion pressure.

8. How can perfusionists detect and correct a malpositioned arterial cannula?

- Regular monitoring of arterial line pressures, flow dynamics, and intraoperative imaging can help detect malposition and prompt repositioning.

9. What is the significance of systemic vascular resistance (SVR) in CPB?

- SVR is crucial for maintaining perfusion pressure; low SVR can lead to hypotension and requires vasopressor support.

10. Why is preoperative briefing important in cardiac surgery?

- Preoperative discussions ensure that all team members are aligned on the patient’s condition, procedural details, and anticipated challenges, improving overall surgical outcomes.

Conclusion

Hypotension on CPB is a serious yet preventable complication that underscores the importance of standardized procedures, meticulous teamwork, and robust communication. By implementing structured checklists, fostering team coordination, and maintaining strict adherence to protocols, surgical teams can significantly reduce the likelihood of critical errors. The case presented serves as a reminder that even minor deviations from routine practices can lead to significant intraoperative challenges, reinforcing the need for vigilance and collaboration in cardiac surgery.

Disclaimer

This article is intended for informational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Cardiperf.com does not take responsibility for any clinical decisions made based on the content provided. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider regarding any medical conditions or concerns.

About Cardiperf.com

Cardiperf.com is dedicated to providing the latest insights, research, and discussions in the field of perfusion sciences and cardiac surgery. Our goal is to support perfusionists, cardiac surgeons, and healthcare professionals with high-quality, evidence-based information to enhance patient care and clinical outcomes.