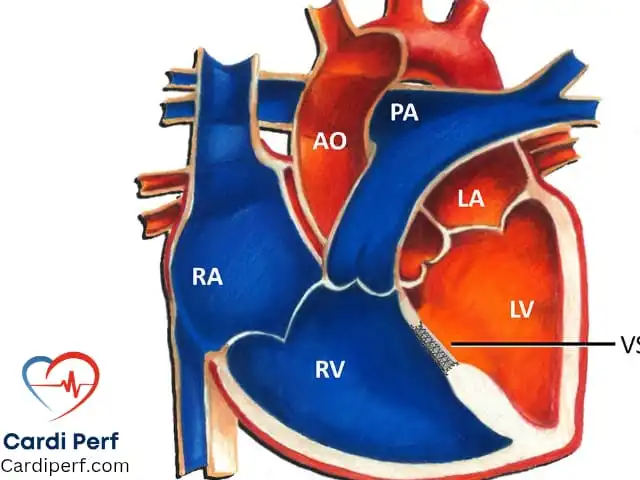

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) is one of the most prevalent congenital heart defects, accounting for a significant percentage of pediatric cardiac cases. It is characterized by an abnormal opening in the interventricular septum, which separates the left and right ventricles of the heart. This defect results in the left-to-right shunting of blood, leading to an increase in pulmonary blood flow and potential long-term complications. Early detection, precise surgical intervention, and optimal perfusion management are essential to ensure a positive outcome for patients with VSD.

For more expert insights on perfusion science, cardiac surgery, and congenital heart defects, visit CardiPerf.com.

Types of VSDs:

VSDs are classified based on their location in the interventricular septum. Understanding the type of VSD is critical for determining the appropriate treatment approach, including the choice of surgical technique and perfusion strategies.

- Perimembranous VSD:

- Most common type (~75%).

- Located near the tricuspid and aortic valves.

- Often associated with the risk of aortic valve distortion, which may complicate repair.

- Muscular VSD:

- Found in the lower part of the septum and typically involves multiple defects.

- Frequently closes spontaneously, though surgical intervention may be required if the defect persists or causes symptoms.

- Outlet (Conal/Subarterial) VSD:

- Located near the outflow tracts of the pulmonary and aortic valves.

- Less common but often requires surgical closure due to its proximity to important cardiac structures.

- Inlet VSD:

- Found near the atrioventricular valves.

- Often associated with atrioventricular septal defects (AVSDs) and conditions like Down syndrome.

Hemodynamics & Pathophysiology:

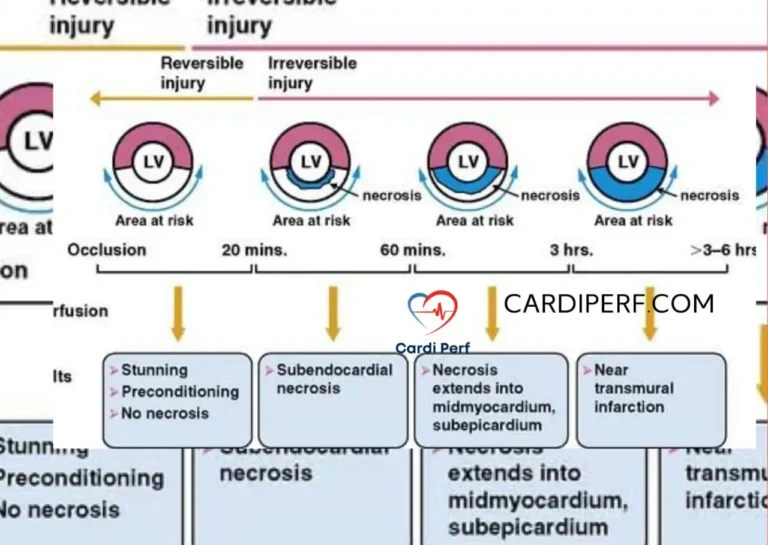

In cases of moderate to large VSDs, blood shunts from the higher-pressure left ventricle into the lower-pressure right ventricle. This increases pulmonary blood flow, leading to pulmonary overcirculation. Over time, this volume overload causes dilation of the left atrium (LA) and left ventricle (LV), which can progress to heart failure.

Without intervention, untreated large VSDs may lead to Eisenmenger syndrome. This condition is marked by the development of pulmonary hypertension, which eventually reverses the direction of the shunt, causing a right-to-left shunt and resulting in cyanosis.

Clinical Presentation:

The clinical manifestations of VSD vary depending on the size and location of the defect:

- Small VSDs (“Restrictive”): These defects may remain asymptomatic and are often detected only by a murmur during a routine physical examination. A loud holosystolic murmur is typically heard at the left lower sternal border.

- Moderate VSDs: These can cause feeding difficulties, failure to thrive, tachypnea, and frequent respiratory infections.

- Large VSDs (“Non-restrictive”): These defects lead to severe heart failure symptoms, including poor growth, cyanosis, and signs of pulmonary hypertension. Eisenmenger syndrome can also develop if left untreated.

Diagnostic Approach:

- Echocardiography with Doppler – This remains the gold standard for diagnosing VSD, assessing the size of the defect, and evaluating the direction and volume of shunting.

- Electrocardiography (ECG) – In larger VSDs, the ECG may reveal left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) or even biventricular hypertrophy.

- Chest X-ray – Cardiomegaly and increased pulmonary vascular markings are common findings in patients with large VSDs, particularly those with pulmonary overcirculation.

- Cardiac Catheterization – Indicated in cases where more precise measurements of pulmonary artery pressures and pulmonary vascular resistance are needed, particularly when Eisenmenger syndrome is suspected.

Management & Treatment:

Medical Management:

- Diuretics (e.g., Furosemide) to manage fluid overload and reduce pulmonary congestion.

- ACE inhibitors or afterload reduction agents to reduce left-to-right shunting and improve myocardial efficiency.

- Nutritional support with high-caloric feeds for patients with failure to thrive.

Surgical Management:

- Small VSDs: These often close spontaneously and require only regular monitoring with echocardiography. Surgical intervention is not generally necessary unless complications arise.

- Moderate to Large VSDs: Surgery is required when the defect leads to significant symptoms or complications such as heart failure or pulmonary hypertension. Indications for surgery include:

- Failure to thrive despite medical therapy.

- The presence of significant pulmonary hypertension.

- Significant dilation of the left heart chambers.

- Prevention of the progression to Eisenmenger syndrome.

Surgical Techniques:

The surgical approach depends on the location and size of the VSD:

- Open-Heart Surgery (Primary Patch Closure):

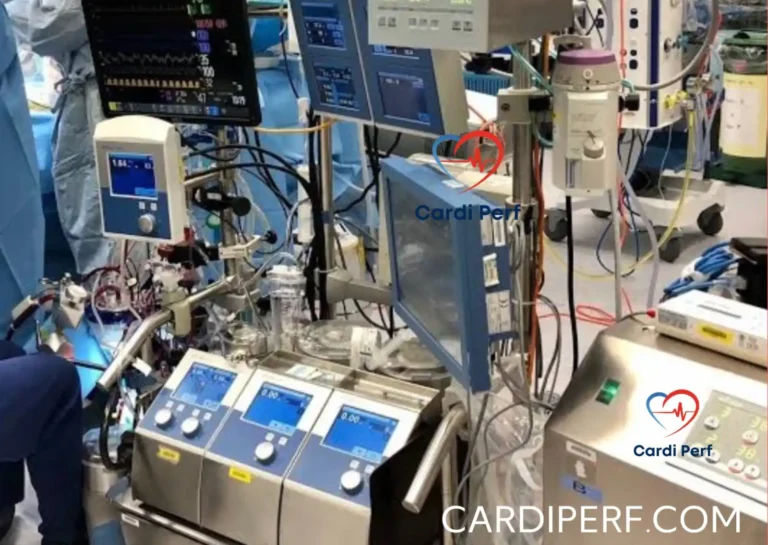

- Performed under cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).

- A synthetic patch (e.g., Dacron) or pericardial patch is used to close the VSD.

- This requires aortic cross-clamping and the administration of cardioplegia for myocardial protection.

- The success of the surgery depends on the precise placement of the patch to avoid complications like residual shunting or valve distortion.

- Transcatheter Closure:

- An emerging technique used for select patients, particularly those with perimembranous or muscular VSDs.

- This technique avoids the need for cardiopulmonary bypass and is performed through a catheter-based approach, often guided by echocardiography.

Perfusion Management During VSD Repair:

Perfusionists play a crucial role in managing CPB during VSD repair. The following considerations are essential:

- Moderate Hypothermia: Maintaining body temperature between 28-32°C helps reduce metabolic demand during surgery.

- Ventricular Decompression: Venting the left ventricle via the right superior pulmonary vein is essential to avoid left ventricular distension during surgery.

- Antegrade Cardioplegia: Used for myocardial protection, ensuring the heart remains protected throughout the surgery.

- Perfusion Pressure: Maintaining an optimal perfusion pressure (around 50-60 mmHg) ensures adequate systemic perfusion while avoiding excessive pulmonary flow during the repair.

Weaning from CPB:

- Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is used to assess for any residual shunting or complications.

- Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) may be managed using medications like nitric oxide or phosphodiesterase inhibitors.

- Modified ultrafiltration (MUF) can be used post-bypass to manage fluid overload and optimize patient recovery.

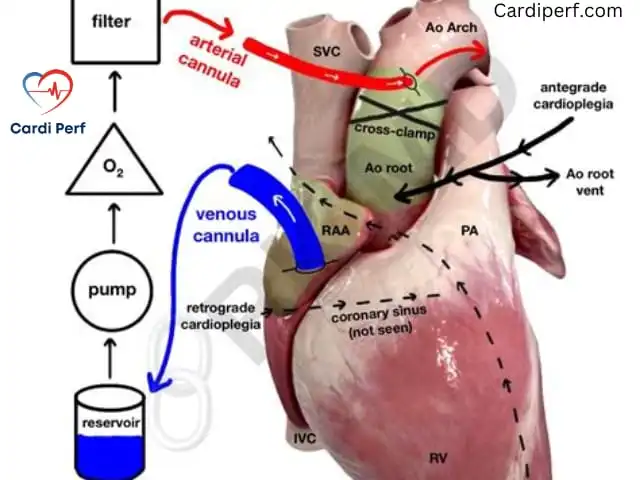

Cannulation Techniques & Selection for Perfusionists:

Selecting the appropriate cannulation technique is essential for ensuring effective CPB and adequate perfusion. The strategy should be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and surgical complexity:

- Aortic Cannulation: The most common approach, where the arterial cannula is placed in the ascending aorta to ensure optimal systemic perfusion.

- Venous Cannulation: A single right atrial cannula is typically used for smaller VSDs, whereas bicaval cannulation is preferred for larger defects to ensure full venous drainage.

- Ventricular Venting: A left ventricular vent through the right superior pulmonary vein helps prevent LV distension during surgery, especially in cases with significant left-to-right shunting.

- Peripheral Cannulation: For reoperative cases or high-risk patients, femoral or axillary cannulation may be used as an alternative or backup, including for ECMO support if needed.

Postoperative Care & Perfusion Monitoring:

- Hemodynamic Monitoring: Ensure stable cardiac output (CO) and assess for signs of low-output syndrome.

- Pulmonary Artery Pressure (PAP): Continuous monitoring for pulmonary hypertension and the need for interventions like nitric oxide therapy.

- Ventilation Strategy: Employ controlled lung recruitment maneuvers to optimize oxygenation and avoid hyperoxia, which can worsen pulmonary hypertension.

ECMO Consideration: In rare cases of severe ventricular dysfunction or persistent pulmonary hypertensive crises, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be required to support the patient until recovery.

Prognosis & Long-Term Outcomes:

- Early Intervention: Most patients who undergo early repair of their VSD lead normal, healthy lives post-surgery.

- Eisenmenger Syndrome: In patients who present late or those who remain untreated, the development of irreversible pulmonary vascular disease may occur, often leading to the need for heart-lung transplantation.

- Long-Term Follow-Up: Regular echocardiography is necessary to monitor for residual defects, assess right ventricular (RV) function, and ensure continued normal cardiac function.

Conclusion:

VSD repair requires a multifaceted approach involving careful assessment, surgical expertise, and effective perfusion management. By understanding the hemodynamics, surgical techniques, and perfusion considerations associated with VSD, healthcare providers can achieve optimal outcomes for their patients.

Perfusionists play a pivotal role in managing the complexity of cardiopulmonary bypass, ensuring proper myocardial protection, and maintaining stable hemodynamics throughout the procedure. Cardiac surgeons must focus on selecting the appropriate surgical approach based on the VSD type and the individual patient’s needs, while other healthcare providers need to be involved in preoperative diagnosis and postoperative care to ensure full recovery.

For more expert discussions on perfusion science, ECMO, and cardiac surgery, visit CardiPerf.com.